Articles/Reviews

“A leader with a fine future.”

“Roots is a tremendous accomplishment, and undoubtedly one of the most important and creative jazz albums produced by a violinist in recent history.”

“despite the depths of interlocking lines and structures, everything ceaselessly flows, oft breezy, swingin’, be-boppy while wafting through the hip museum.”

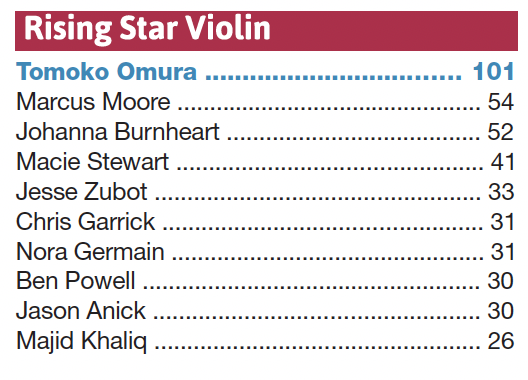

2021 Downbeat

critics’ poll

GRAMMY.com article, May, 2021

recordingacademy IG post in 2021

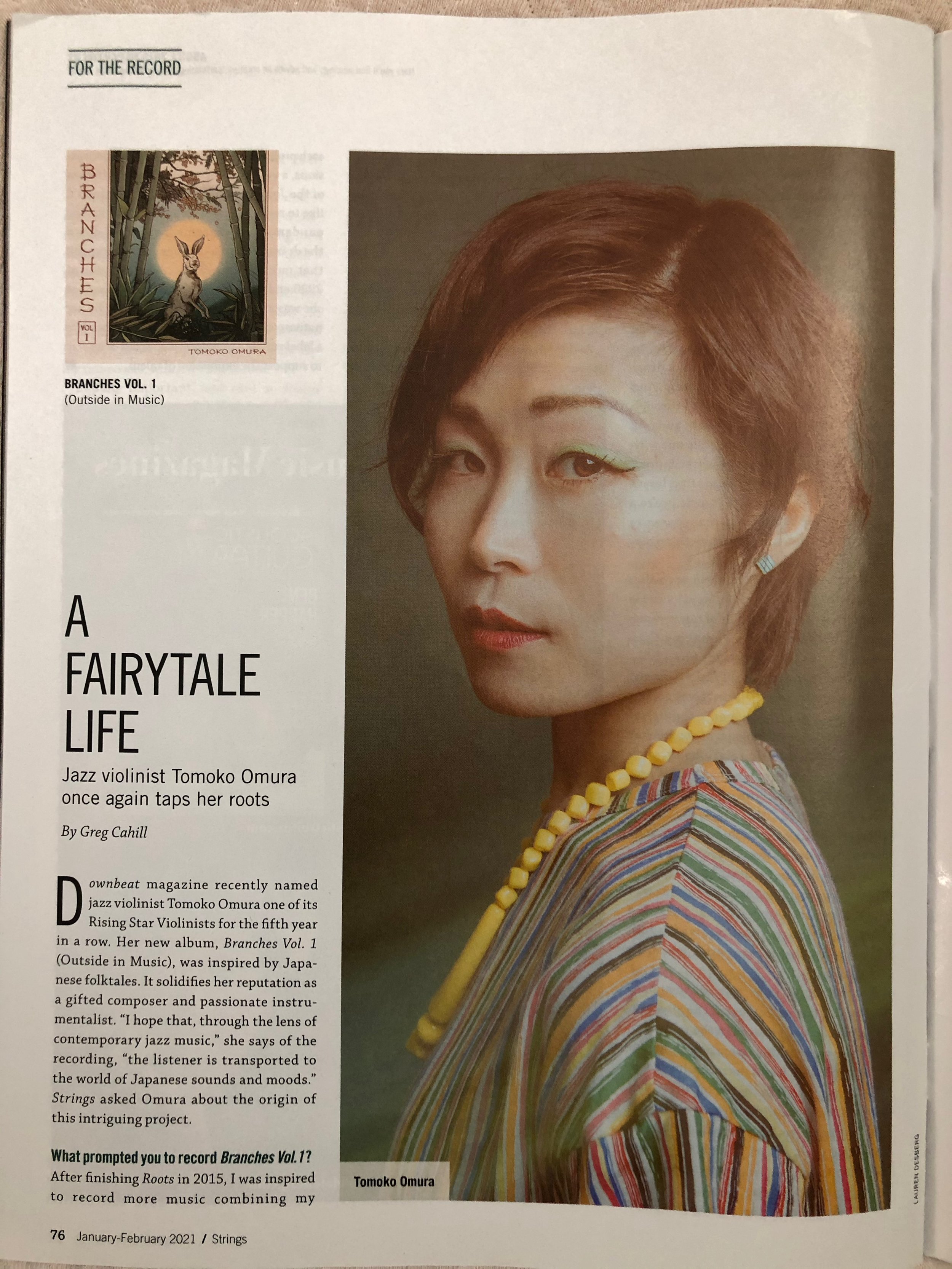

Strings Magazine January-February 2021

“Her swooping lines and emotive outpourings are contemporary without losing the sense of tradition inherent in both Japanese folk and Western jazz - in other words she can swing!”

“Rhythmically vibrant and melodically satisfying, Omura merges two distinct traditions with passion and panache; the result is music that’s bold in design and beautiful in execution.”

“swinging with élan while gently incorporating elements of rock, chamber, and other influences into a pleasing aesthetic.”

“Omura masterfully injects her bold and contemporary blend of jazz into these Japanese standards to create a new and refreshing sound she can proudly call her own.”

AllAboutJazz article "Roots and Branches" by Ian Patterson

It's been a good year for New York-based, Japanese violinist/composer Tomoko Omura, whose second CD as leader, Roots (Inner Circle Music), has earned high praise from critics and peers alike. The roots of the title refer to Omura's heritage as she reimagines popular Japanese tunes through the prism of jazz. The ten tracks draw inspiration from film themes, folk tunes and even the national anthem—material familiar to and beloved of successive generations of Japanese. Yet Omura's idiom is pure jazz, and with the backing of her regular New York band she has crafted what violin maestro Christian Howes has described as "one of the most beautiful, important, creative and relevant works of jazz violinists in the recent past."

Clearly Howe isn't the only one impressed by Omura's musicianship and skills as an arranger, as she was voted as a Rising Star in Downbeat Magazine in July. It might seem like 2015 is a breakthrough year for Omura but that's not how the unassuming musican sees it: "Maybe it looks that way but I don't really feel that way," she says. "I've been doing the same thing -working on music, playing with my band and playing with other bands. My life is not really different."

After ten years in America, Omura's life is undoubtedly a whole lot different to when she was a student in Japan, dreaming of a passage to America to pursue her love of jazz. That Omura didn't go down the classical music path may seem odd, given that she began the violin aged just four and given her family background. "The strongest memory I have was when I was eleven or so, in Vienna, Austria," Omura recalls. "My mother was in the Shizuoka Symphony and they travelled there to play a Tchaikovsky violin concerto. I remember thinking 'Oh wow! This is great!' It was one of the most impressive concerts I've ever been to. It was beautiful, though I never particularly wanted to play that music."

Though Omura and jazz were star-crossed lovers destined to meet eventually, her introduction to this universe came close to home while she was still in junior high school.: "My older brother, Hiroyuki, started playing Jimi Hendrix and Jaco Pastorius and Miles Davis and all that music with his friends. He played drums and sometimes bass. One day I heard this great music from his room so I ran and knocked his door and asked "What's that music?" It was Kind of Blue (Columbia, 1959) by Miles Davis. That was the first time I ever listened to jazz and I just fell in love."

From there, Omura's path towards jazz followed a logical—though by no means easy—route when she later went to Yokohama National University. "I knew about the student organisation called the Modern Jazz Society, where students gather together and play jazz, but there's no teacher. In Japan it's pretty famous because some of the students become professional jazz musicians, so I wanted to be in that scene," Omura explains. "That's part of the reason I chose that university."

Early inspiration for Omura came from various sources: "I knew about Stephane Grappelli first and that gave me the encouragement -it's okay to play jazz with violin. I respect him though I wasn't so much into his musical style. Then I discovered Jean-Luc Ponty and I was really into his music."

Closer to home, Omura found a style of jazz violin more on her wavelength in violinist Naoko Terai, who has collaborated with Kenny Werner, Lee Ritenour and Richard Galliano. "She had just released her first album [Thinking of You, 1998] when I started playing jazz," relates Omura, "and I thought, 'Oh, there is modern jazz violin!' I was into that scene."

Omura's ambitions, however, didn't rest in Yokohama's Modern Jazz Society. Her eyes were on the Berklee College of Music, Boston—a seemingly impossible dream. "I was hoping to get a scholarship," Omura explains, "because if I didn't get one I couldn't afford to go, so I'm glad that it happened."

The young violinist made her way to Berklee in 2004, full of excitement and hope. Within no time at all she had made her mark, winning BCM's Roy Haynes Award for outstanding improvisational skills—the first time this honor had been given to a violinist. At Berklee, Omura studied with George Garzone, Hal Crook, Ed Tomassi and Matt Glaser.

Glaser, a versatile jazz and bluegrass violinist and currently Artistic Director of Berklee's American Roots Music Program, would introduce Omura to one of her most important influences when he played her a recording of Polish violinist Zbigniew Seifert. "That changed my world," says Omura. "I didn't know about Zbigniew when I was in Japan. Matt Glaser played this solo violin album [Solo Violin EMI, 1976] and he said, 'OK, try transcribing this.'"

Like any good student, Omura dutifully made the transcription of Seifert's music. The rewards were significant. "I fell in love musically. I had never heard that intensity and such modern language on the violin." Having graduated cum laude from Berklee in 2007, Omura wasted little time in recording her debut CD, Visions (Self Produced, 2008). A personal homage to jazz violin greats, Omura's original compositions acknowledged Grappelli, Stuff Smith, Mark Feldman, Ponty, Didier Lockwood, Joe Venuti, and, with the simply titled "Zbigniew"—Seifert.

Born in Krakow in 1946, Seifert played with Tomasz Stanko from the mid-1960s, recording several albums with the trumpeter. Seifert would make a handful of outstanding recordings of his own that featured the likes of Hans Koller, Joachim Kuhn, Cecil McBee, John Scofield, Billy Hart, Jack DeJohnette and Oregon. Those who played with him declare him to have been something of a musical genius—a one-off.

Tragically, Seifert died of cancer in 1978, aged thirty two, and only recently with the release of his old recordings on CD is he beginning to reach a new generation of musicians, such as Omura. "There's a strong message in Seifert's music," she says. "I was blown away."

Fast forward half a dozen years to 2014 when Omura made a pilgrimage of sorts to Poland to participate in the inaugural Zbigniew Seifert International Jazz Violin Competition: "I don't think that playing music should be competitive and I would never enter another competition," Omura says, laughing. "I did this one because the competition was in Zbigniew Seifert's name. I had wanted to go to Poland for a long time to see where he was from."

Though Omura didn't win the competition she took away many positives from her participation: "I met many great people there, great violinists, supporters of jazz violin and fans of Zbigniew. I even met Zbigniew's wife, who was very supportive."

Musically, Omura also benefitted from the competition: "The experience challenged me and helped me find out what I want to say in music."

If on her critically acclaimed debut Visions Omura's drew from and expressed herself in a familiar yet striking jazz idiom, her follow-up is perhaps more of a personal statement, drawing as it does from her own cultural heritage—her deepest roots.

The origin of Roots goes back to a Japanese tour Omura was undertaking back in 2009 to promote Visions: "When I played in my hometown of Shizuoka, though, I arranged a Shizuoka folk song for that particular performance," Omura relates. "The audience knew the melody and reacted with such feeling. It was a great experience and I couldn't forget about it. I started to think it would be nice to do an album of all Japanese folk songs."

The playing on Roots is tight yet flowing, disciplined and exploratory. Much of the music's success music lies in the chemistry between Omura and guitarist Will Graefe, pianist/keyboardist Glenn Zaleski, double bassist Noah Garabardian and drummer Colin Stranahan. The band had already been together several years and it shows in the collective energy and brio with which they address Omura's arrangements.

"Everyone is a strong individual. I don't tell them what to do," says Omura. "They just do what they do. I bring the music and the charts and everything but they can get imaginative and bring their own thing, so that's the best part."

The song selection on Roots reflects melodies popular to several generations of Japanese, including, perhaps surprisingly, a lyrical take on the national anthem: "I had an idea to open and close the album with the Japanese national anthem as a tribute to Japanese people," explains Omura. "It didn't happen but I knew I was going to use it, in a little bit more stretched way."

It's a an approach Omura has taken with all the tunes, for with the exception of the sound of the tea-pouring ceremony that introduces the traditional "Cha Tsu Mi" (Green Tea Picking), there is little to suggest—to the unfamiliar Western ear at least—that these are famous Japanese tunes reimagined. The one tune that may ring a bell with jazz buffs is "Kojo No Tsuki (Castle in the Moonlight"), which Thelonious Monk recorded on Straight No Chaser (Columbia, 1967). Omura's arrangement, however, was not intended as a tribute to the great pianist: "I actually hadn't heard it [Monk's version], though when I started playing it with people they told me 'have you checked out...?' "

Early in 2015, Omura toured Japan with Roots in a quartet consisting of Zaleski, bassist Daiki Yasukagawa and drummer Ryo Shibata. Audience's reactions to Omura's jazz reworking of Japanese tunes were very positive: "When I was introducing the songs we were going to play people were like, 'Wow! You're going to play that? In a jazz club?' From the beginning they were very interested," relates Omura. "Some of them were not jazz fans so it was a good way to connect to different generations."

The Shizuoka gig, was needless to say, a special occasion: "It was great," says Omura. "Of course, in my hometown some people have known me since I was very little so it's like family. Some of them come every year to my concerts at home and I try to be a better musician."

In striving to be a better musican Omura uses her time to the best advantage: "Nowadays I practise a lot, whenever I can find the time. Sometimes I only practise in my head, while I'm walking outside," explains Omura. "I practise the improvisation in my head—how I want to make the phrases or a certain patterns that I want to learn—I'll practise in the head first and then I'll play it on my instrument. I like doing that walking outside; I feel freer than in a room. When you take the subway you can practise. It's helpful."

Like many musicians, Omura also teaches to help meet the rent, taking the same care with teaching as she does with making music. "I try to make the lessons as creative as possible which is the way I approach music in general," the violinist explains.

"I think it's very important to be creative and flexible, playing-wise and teaching-wise," Omura expands. "I myself wasn't solidly classically trained in Japan. I didn't go to the conservatory. I learned from my Mom—who is a classical violinist—but our lessons were basic and she wasn't training me to become a classical soloist. So, I think that kind of looseness made me really get into jazz and rock when I was a teenager. I liked that openness. It's very important to be open-minded."

On Roots the strands of rock and classical music in Omura's DNA are woven subtly into the mix but in New York the violinist also plays in a broad range of settings, from a one-off gig with Gregg Bendian's Mahavishnu Project at The Stone to the old-style jazz of Carte Blanche, an events band that plays the jazz of the 1920's to the 1950s. "I enjoy it," says Omura of Carte Blanche. "I try to approach it the same way I do with my music. I try to stay in the same mind-set. Sometimes playing at the parties it's difficult because maybe no-one is listening. But that's challenging too."

Then there's String Bop Trio: "That plays more bebop repertoire, with violin, guitar and bass. I like that instrumentation but I want to stretch that project a little more, compose original music and record at some point. That one is still developing."

More definitely Omura is already working on a follow-up to Roots: "The Roots project is still on-going. There are so many good songs in Japan that I couldn't include everything on the first album. I've been composing more music and I have about half an album -maybe five songs already. I'd like to record that when I'm ready."

When the time comes, Omura will more than likely once again release the next chapter in the Roots project on Greg Osby's label Inner Circle Music. The label's dedication to encouraging original, creative music chimes with Omura: "There are no restrictions, no limitations. I really like that part of the label. You can do pretty much whatever you want."

In spite of the Downbeat recognition and the glowing reviews for Roots it has proved hard getting gigs for the Roots quintet in New York and beyond: "It's very difficult," Omura acknowledges. "I'm having a tough time, budgeting and so on. It takes patience and a lot of time and effort. I'm still learning how to do that in this society."

Nobody said that making it as a jazz musician in New York would be easy, but Omura, more than a decade into her American adventure and with two excellent recordings under her belt, is not only making a good go of it but, importantly, has no fear: "Sometimes hardships work as fuel," Omura says philosophically. "I don't want to go the easier way because I know I would be bored. I like challenges."

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/tomoko-omura-the-roots-of-the-matter-tomoko-omura-by-ian-patterson.php